Silkroad

What

is Silkroad?

The Silk Road or Silk Route is a term which refers to the complex historical

network of ancient trade routes across the Afro landmass of Eurasian which

connected East, South, and Western Asia with the Mediterranean and European

world in the past and to some extent even today. It also connected parts of

North and East Africa. Making the route Extending to 4,000 miles or 6,500

kilometers. The name Silk Road originates from the lucrative Chinese silk trade

along this wide route. Silk trade began during the Han Dynasty (206 BC –

220 AD) during 114BC the central Asian sections of the trade routes were

expanded as per the the missions and explorations of Zhang Qian.

Trade on the Silk Road played a significant role in the development of the

civilizations of China, Pakistan, India, Persia, Europe and even Arabia. Not

only Silk was traded but the route also transported many other goods. Besides

trade the Silkroad also helped transfer various technologies, religions and philosophies,

culture, art, historical records as well as the bubonic plague

(the "Black Death"), also traveled along the Silk Routes.

The route was used earlier times by Indian and Bactrian traders, then

from the 5th to the 8th century the Sogdian traders, then afterward the Arab and

Persian traders.

History of Silkroad ,

Silkroad Tours

What

were the routes of Silkroad?

What

were the routes of Silkroad?

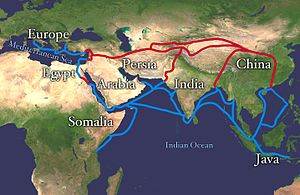

The antique Silk Road was spread on a huge mass of the Afro-Eurasian mass

thus there were several routes which all combined made this gigantic route of

4000 miles or 6500 Kilometer although his figure itself is very humble the route

must have been even longer taking note of 3 distinct routes all together

Overland routes (See the red lines in

the map on right)

On westwards from the ancient commercial centers of China, the

overland, intercontinental Silk Road divided into two routes the northern and southern

routes after passing the Taklimakan Desert and Lop Nur. Northern route went

through the central Asia and the southern route through the high mountains of

Pakistan

Northern Route

The northern route started at Chang'an (now called Xi'an n China), Chang'an

was the capital of the

ancient Chinese Kingdom however later in Han dynasty the capital was moved further east to Luoyang. The route was defined about the 1st century BC as Han Wudi

in order to put an end

to harassment by nomadic tribes along the route.

The northern silk route crossed northwest through the Chinese province of Gansu

from Shaanxi Province, and split into three further routes, two following the mountain ranges to the north and south of the Taklamakan Desert to

rejoin at Kashgar; and the other going north of the Tian Shan mountains through

Turpan, Talgar and Almaty (in what is now southeast Kazakhstan). The routes

split again west of Kashgar, with a southern branch heading down the Alai Valley

towards Termez (in modern Uzbekistan) and Balkh (Afghanistan), while the other

traveled through Kokand in the Fergana Valley (in present-day eastern

Uzbekistan) and then west across the Karakum Desert. Both routes joined the main

southern route before reaching Merv (Turkmenistan).

The northern route was ideal for for caravans as the mountain passes are much

easier there. This part of Silk Road brought to China many goods such as "dates,

saffron powder and pistachio nuts from Persia; frankincense, aloes and myrrh

from Somalia; glass bottles from Egypt, and other expensive and desirable goods

from other parts of the world." In exchange, the caravans

sent back bolts of silk brocade, lacquer ware and porcelain. Another branch of

the northern route turned northwest past the Aral Sea and north of the Caspian

Sea, then and on to the Black Sea.

Southern Route

Southern Route

The southern route or Karakoram route was mainly a single route running from

China, through the Karakoram mountains, where it persists to modern times as the

international paved road the Karakorum Highway

connecting Pakistan and China.

It then set off westwards, but with southward spurs enabling the journey to be

completed by sea from various points in southern Pakistan's Sindh. Crossing the high mountains, it passed

through northern Pakistan, over the Hindu Kush mountains, and into Afghanistan,

rejoining the northern route near Merv. From there, it followed a nearly

straight line west through mountainous northern Iran, Mesopotamia and the

northern tip of the Syrian Desert to the Levant, where Mediterranean trading

ships plied regular routes to Italy, while land routes went either north through

Anatolia or south to North Africa. Another branch road traveled from Herat

through Susa to Charax Spasinu at the head of the Persian Gulf and across to

Petra and on to Alexandria and other eastern Mediterranean ports from where

ships carried the cargoes to Rome.

South-west Route

The southwest route is believed to be the Ganges/Brahmaputra Delta which has

been the subject of international interest for over two millennia. Strabo, the

1st Century Roman writer, mentions the deltaic lands: ‘Regarding merchants who

now sail from Egypt…as far as the Ganges, they are only private citizens...’ His

comments seem to be interesting since the Roman beads and other materials are

being found at Wari-Bateshwar ruins, the ancient city with roots from much

earlier before the Bronze Age presently being slowly excavated beside the Old

Brahmaputra in Bangladesh. Ptolemy’s map of the Ganges Delta, a remarkably

accurate piece of mapping, showed quite clearly that his informants knew all

about the course of the Brahmaputra River, crossing through the Himalayas then

bending westward to its source in Tibet. It is doubtless that this delta was a

major international trading center, almost certainly from much earlier than the

Common Era.

Gemstones and other merchandise from Thailand and Java were traded

in the delta and through it. A famous Chinese archaeological writer Bin Yang,

whose work, ‘Between Winds and Clouds; The Making of Yunnan’, published in 2004

by the Columbia University press and some earlier writers and archaeologists,

such as Janice Stargardt strongly suggest this route of international trade as

Sichuan-Yunnan-Burma-Bangladesh route. According to Bin Yang, especially from

the 12th century the route was used to ship bullion from Yunnan (Gold and Silver

being among the minerals in which Yunnan is rich), through northern Burma, into

modern Bangladesh, making use of the ancient route, known as the ‘Ledo’ route.

The emerging evidence of the ancient cities of Bangladesh, in particular

Wari-Bateshwar ruins, Mahasthangarh, Bhitagarh, Bikrampur, Egarasindhur and

Sonargaon are believed to be the international trade centers in this route.

Impacts of Silkroad on the world

Silkroad had great influence over the cultures of the world. The stories of

merchants and their goods all mingled cultures and new dimensions of life were

exchanged between the people of far off countries. it also brought religions,

philosophies and literature from East to West and West to East

Cultural exchanges

Cultural exchanges

Richard Foltz, Xinru Liu and others have described how trading activities

along the Silk Road over many centuries facilitated the transmission not just of

goods but also ideas and culture, notably in the area of religions.

Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, Manichaeism, and Islam all

spread across Eurasia through the Silkroad and other trade routes. The spread of religions and cultural traditions

along the Silk Roads, according to Jerry H. Bentley, also led to syncretism. One

example was the encounter with the Chinese and Xiongnu nomads. These unlikely

events of cross-cultural contact allowed both cultures to adapt to each other as

an alternative. The Xiongnu adopted Chinese agricultural techniques, dress

style, and lifestyle. On the other hand, the Chinese adopted Xiongnu military

techniques, some dress style, and music and dance. Of all the cultural

exchanges between China and the Xiongnu, the defection of Chinese soldiers was

perhaps the most surprising. They would sometimes convert to the Xiongnu way of

life and stay in the stepps for fear of punishment

Transmission of art

Many artistic influences were transmitted via the Silk Road, particularly

through Central Asia, where Hellenistic, Iranian, Indian and Chinese influences

could intermix. Greco-Buddhist art represents one of the most vivid examples of

this interaction.

These artistic influences can also be seen in the development of Buddhism,

where, for instance, Buddha was first depicted as human in the Kushan period.

Many scholars have attributed this to Greek influence. The mixture of Greek and

Indian elements can be found in later Buddhist art in China and throughout

countries on the Silk Road.

Foltz, Richard C. (1999). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and

Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century. New York: St Martin’s

Press. p. 45.

Transmission of Buddhism

Transmission of Buddhism

The transmission of Buddhism to China via the Silk Road began in the 1st

century AD, according to a semi-legendary account of an ambassador sent to the

West by the Chinese Emperor Ming (58–75 AD). During this period Buddhism began

to spread throughout Southeast, East, and Central Asia. The Buddhist movement was the

first large-scale missionary movement in the history of world religions.

Buddha’s community of followers, the Sangha, consisted of male and female monks

and laity. These people moved through India and beyond to spread the ideas of

Buddha. Extensive contacts started in the 2nd century AD, probably as a

consequence of the expansion of the Kushan empire into the Chinese territory of

the Tarim Basin, due to the missionary efforts of a great number of Central

Asian Buddhist monks to Chinese lands. The first missionaries and translators of

Buddhists scriptures into Chinese were either Parthian, Kushan, Sogdian or

Kuchean.

One result of the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road was displacement and

conflict. The Greek Seleucids were exiled to Iran and Central Asia due to a new

Iranian Dynasty called the Parthians at the beginning of the 2nd century BCE,

and as a result the Parthians became the new middle men for trade in a period

when the Romans were major customers for silk. The Parthians were Buddhists and,

because they found themselves in a main trade centre on the Silk Road, the city

of Marv became a major Buddhist centre by the middle of the 2nd century.

Knowledge among people on the silk roads also increased when Emperor Ashoka of

the Maurya dynasty (268-239 BCE) converted to Buddhism and raised the religion

to official status in his northern Indian empire.

From the 4th century onward, Chinese pilgrims also started to travel on the Silk

Road to India, in order to get improved access to the original Buddhist

scriptures, with Fa-hsien's pilgrimage to India (395–414), and later Xuan Zang

(629–644) and Hyecho, who traveled from Korea to India. The legendary

accounts of the holy priest Xuan Zang were described in a novel called Journey

to the West, which told of trials with demons, but also the help of various

disciples on the journey.

From the 4th century onward, Chinese pilgrims also started to travel on the Silk

Road to India, in order to get improved access to the original Buddhist

scriptures, with Fa-hsien's pilgrimage to India (395–414), and later Xuan Zang

(629–644) and Hyecho, who traveled from Korea to India. The legendary

accounts of the holy priest Xuan Zang were described in a novel called Journey

to the West, which told of trials with demons, but also the help of various

disciples on the journey.

There were many different schools of Buddhism travelling on the Silk Road. The

Dharmaguptakas and the Sarvastivadins were two of the major nikaya schools.

These were both eventually displaced by the Mahayana, also known as “Great

Vehicle”. This movement of Buddhism first gained influence in the Khotan region.

The Mahayana, which was more of a “pan-Buddhist movement” than a school of

Buddhism, appears to have begun in north western India or Central Asia. It was

small at first and formed during the 1st century BCE, and the origins of this

“Greater Vehicle” are not fully clear. Some Mahayana scripts were found in

northern Pakistan but the main texts are still believed to have been composed in

Central Asia along the Silk Road. These different schools and movements of

Buddhism were a result of the diverse and complex influences and beliefs on the

Silk Road.

During the 5th and 6th centuries BCE, Merchants played a large role in the

spread of religion, in particular Buddhism. Merchants found the moral and

ethical teachings of Buddhism to be an appealing alternative to previous

religions. As a result, Merchants supported Buddhist Monasteries along the Silk

Roads and in return the Buddhists gave the Merchants somewhere to stay as they

traveled from city to city. As a result, Merchants spread Buddhism to foreign

encounters as they traveled.[43] Merchants also helped to establish diaspora

within the communities they encountered and overtime their cultures became based

on Buddhism. Because of this, these communities became centers of literacy and

culture with well-organized marketplaces, lodging, and storage. The Silk

Road transmission of Buddhism essentially ended around the 7th century with the

rise of Islam in Central Asia.

Advertise on this site click for advertising rates