Across the Durand Line

What is Durand Line

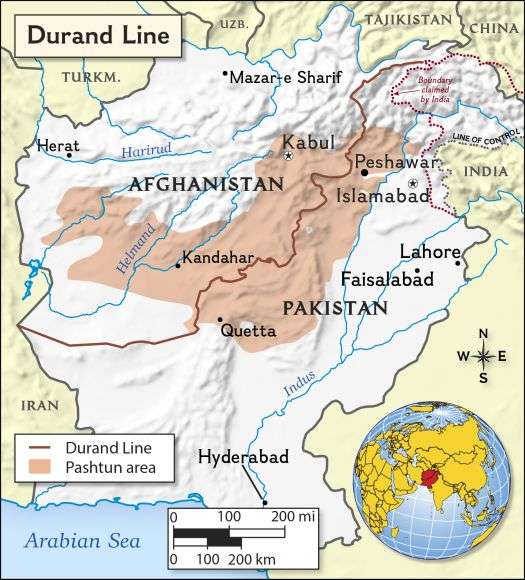

The Durand Line is the 2,640-kilometer (1,640-mile) border between

Afghanistan and Pakistan. It’s the result of an agreement between Sir Mortimer

Durand, a secretary of the British Indian government, and Abdur Rahman Khan, the

emir, or ruler, of Afghanistan. The agreement was signed on November 12, 1893,

in Kabul, Afghanistan.

The Durand Line as served as the official border between the two nations for

more than one hundred years, but it has caused controversy for the people who

live there.

When the Durand Line was created in 1893, Pakistan was still a part of India.

India was in turn controlled by the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom ruled

India from 1858 until India’s independence in 1947. Pakistan also became a

nation in 1947.

Across the Durand Line

Owen Bennett-Jones

The Pashtun Question: The Unresolved Key to the Future of Pakistan and

Afghanistan

by Abubakar Siddique.

Hurst, 271 pp., £30, May 2014, 978 1 84904 292 5

The Taliban Revival: Violence and Extremism on the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier

by Hassan Abbas.

Yale, 280 pp., £18.99, May 2014, 978 0 300 17884 5

The conflict in the Afghanistan-Pakistan borderlands has similarities with

other contemporary struggles. From Timbuktu to Kandahar, jihadis, national

governments, ethnic groups and, in some cases, tribes are fighting for

supremacy. In each place there are complicating local factors: badly drawn

international borders; the relative strength or weakness of non-violent Islamist

movements; the presence or absence of foreign forces, whether Western or jihadi;

and different historical experiences of colonialism. From the point of view of

Western policymakers some of these conflicts seem to be more important than

others. For the French, the potential fall of Mali to radical Islamist forces

was unacceptable, so they intervened. In Somalia, by contrast, the problem has

largely been ignored by the West and is mostly being dealt with by the African

Union. It was said that al-Qaida must not be allowed to hold territory in Syria,

but both an al-Qaida affiliate and Isis have been doing just that, and it wasn’t

until earlier this month that Obama announced he’d strike Isis from the air.

It’s far from clear that these varied responses to jihadi activity are the

result of rational decision-making. In Yemen, for example, al-Qaida supporters

move about freely and plot attacks against the West. Yet although the US has

used air power in Yemen it has for the most part left the fighting to the far

from capable Yemeni armed forces. But the Pashtun areas of the

Afghanistan-Pakistan borderlands are an exception to the mixed messages. There

the West has used every tactic at its disposal to confront jihadis: boots on the

ground, air strikes, drone attacks, bribes, social welfare programmes and

infrastructure projects – the effort to control the Pashtuns hasn’t lacked

commitment. There are, of course, important differences between Yemen and the

Pashtun areas. Attacks organised in Pashtun areas – including 9/11 and 7/7 –

have succeeded; even the most sophisticated plot to emerge from Yemen, in which

bombs were disguised as printer cartridges, was foiled. And it isn’t just that

the US was impelled to avenge 9/11. The outside world is interested in the

Pashtuns’ poppy crop and their hosting of much of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal.

Over the last century and a half the intricacies of Pashtun politics have been

discussed by politicians and their advisers in the capitals of all the Great

Powers: it’s Washington that’s worrying today, but it used to be Moscow, and

before that London.

In 1893 the British created the Durand Line to divide Afghanistan from the

north-west corner of the Raj (now Pakistan). These days Pakistan accepts the

border and Afghanistan doesn’t. The line cuts the Pashtun people in two: roughly

a third of them are in Afghanistan and two-thirds in Pakistan. The Durand Line

had a specific purpose, and governed British policy towards the Pashtuns. This

was not an imperial heartland but a buffer zone and British administrative

arrangements reflected this. Some British-controlled Pashtun areas were declared

‘settled’; others, close to the line, were designated ‘tribal’. The tribal

elders were given subsidies and status: in return, they were expected to keep

the peace and, crucially, to ensure the roads stayed open. And so the military

objective of protecting the edge of the empire was achieved with minimum

resources. Just in case the bribes were insufficient, the elders were further

persuaded to co-operate by the Frontier Crimes Regulation, imposed in 1901. It

had two crucial elements: first, people could be held indefinitely without

charge; second, it allowed collective punishment, meaning that whole communities

could be sanctioned for the crimes of one member.

As some British administrators realised at the time, the system entrenched

tribal structures. It might have been thought that the birth of Pakistan in 1947

would transform the situation, with the new state making efforts to drag the

tribal areas towards more regular constitutional arrangements. In fact little

changed. Collective punishments against the families and communities of

suspected miscreants are still handed down. The Pakistani officials who

implement the system are still called political agents, just like their British

forebears. Their powers remain sweeping and arbitrary. ‘Around here,’ a Khyber

political agent once told me, ‘I am Allah’s deputy.’ On the Afghan side of the

border, too, the central government has never been strong enough to break down

tribal affiliations. On both sides of the Durand Line the result has been

economically and socially disastrous – on the Pakistani side female illiteracy

stands at more than 70 per cent.

The unusual methods of governance in the Pashtun areas became especially

significant after 9/11. When the Taliban and al-Qaida fled Afghanistan in 2001

and 2002, many ended up in Pashtun areas on the Pakistani side of the line. They

took advantage of the fact that jihadis and tribesmen are free to move across it

but the military forces of Washington, Kabul and Islamabad are not. As the war

in Afghanistan ground on, and the Afghan Taliban regrouped, the US had a choice.

It could work with Pakistan’s political agents to bribe and bully tribal elders

to hand over Taliban fighters seeking refuge in Pakistan; or it could use force.

Unwilling to delegate a frontline in the war on terror to a bunch of tribal

administrators, the US deployed soldiers in Afghanistan and drones and special

forces on both sides of the Durand Line. The tribal elders found themselves

squeezed by the forces surrounding them. Should they offer sanctuary to the

jihadis? Or should they capture them and take US money for handing them over? As

they considered their options, the elders took into account the challenges posed

by local political competition, including both religious and nationalist

leaders.

In recent years the religious elements have been in the ascendant, but the

nationalists also have deep roots in the Pashtun areas. The faqir of Ipi, a

Pashtun leader who fought the British in the 1930s, represented both aspects of

Pashtun society. An obscure rural cleric from North Waziristan, he became a

symbol of opposition to the British Empire. The case that thrust him to

prominence has a modern parallel. The story goes that Mullah Omar established

his leadership credentials in the Afghan Taliban by challenging a warlord near

Kandahar who had buggered a local boy. The faqir of Ipi began his career by

complaining about a British Indian court’s ruling against the marriage of a

15-year-old girl to a Muslim man. The court found that the girl, originally a

Hindu, had been converted when she was a minor and so removed her from her

husband. The faqir used the case to unite tribal forces and was soon able to

raise a private army of thousands, drawn from Afghanistan as well as areas under

British control. At this stage, his pitch was religious: he spoke about the

impending doomsday, when only those Muslims who answered his call to action

would gain entry to paradise. His followers believed he could heal the sick and

turn air ordnance into paper. The British practice of airdropping propaganda

leaflets confirmed the faqir’s powers.

When it came to the creation of Pakistan, the faqir, knowing that it would be

difficult to object on religious grounds to a country created in the name of

Islam, opposed it for nationalist reasons. He argued that for the Pashtuns to be

ruled by Pakistanis was hardly better than being ruled by the British. After

1947 he allied himself with the Pashtun nationalist leader Abdul Ghaffar Khan,

whose followers were known as Red Shirts (their uniforms were stained with brick

dust). As the British prepared to leave the subcontinent, Ghaffar Khan’s

anti-imperialist rhetoric resonated throughout the Pashtun areas. To accommodate

the nationalist movement, the British decided to hold a referendum in the

North-West Frontier Province. Ghaffar Khan demanded that as well as offering a

choice between India and Pakistan, the British should allow the Pashtuns to vote

for an independent state, Pashtunkhwa. The government in Kabul argued for a

fourth option: union with Afghanistan. Lord Mountbatten, however, permitted just

two choices: union with India or Pakistan. Ghaffar Khan, desiring neither

outcome, boycotted the vote. Of those who voted, 99 per cent opted for Pakistan.

The nationalist movement didn’t go away. Ten years ago I watched a rally in

north-west Pakistan that was attended by thousands of people wearing red shirts.

The event was organised by the Awami National Party (ANP), the direct political

descendant of Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s movement: it is currently led by his grandson

Asfandyar Wali Khan. Wali Khan has always been careful to ask only for greater

autonomy (Pakistani law forbids open demands for secession), but few doubt that

if Pashtun independence were on offer he would grasp it. The ANP can be seen as

just an obscure regional party with – now – only one member in the National

Assembly. But you could argue that it is one of the most important parties in

Pakistan: unlike most of the others, it articulates liberal values and directly

opposes the Taliban. While everyone else has compromised with the jihadis, the

ANP has taken a stand, and paid a terrible price. Recognising that the ANP is

its main ideological challenger, the Pakistani Taliban has relentlessly targeted

the party’s leaders. As the death toll mounted, the electorate came to see the

ANP as weak and, in the unforgiving world of patronage politics, voters lost

confidence that the party would be able to secure benefits from the government

in Islamabad and so rejected it at the polls. The ANP’s lonely stand against the

religious extremists was further undermined by the central government’s fears

that the party threatens Pakistan’s territorial integrity.

If it was looking for existential threats, Islamabad would have been better

advised to worry about the jihadis. The Pashtun nationalists have always faced

insurmountable obstacles. They are divided between two states – Pakistan and

Afghanistan – that have no intention of giving up territory. Just as the Line of

Control has fatally undermined the attempts of Kashmiri nationalists to break

free of India and Pakistan, so the Durand Line has obstructed the Pashtun

nationalist cause. And by giving senior military and bureaucratic jobs to a few

Pashtuns from prominent families, Islamabad and Kabul have been able to co-opt

potential separatist leaders. Pakistani Pashtuns are now so well represented in

the army and the civil service, and so commercially active in Karachi, that

independence would come at a cost higher than most would be willing to pay.

For all their appeal to many Pashtuns, the nationalists seem doomed to remain

bystanders to another struggle: between the tribal and religious leaderships. At

the time of Pakistan’s creation, the tribal elders had the upper hand. The

mullahs were seen as uneducated, socially inferior functionaries whose main role

was to supervise marriages and funerals. Over the last decade there have been

moments when tribal elders on both sides of the Durand Line (often encouraged by

US bribes) have protected their interests by forming lashkars – private armies –

to fight Taliban forces. All the governments involved in fighting the Taliban

have tried to leverage tribal loyalties, although this policy has the arguably

counterproductive effect of entrenching the tribal structures that have held

back social and economic development: in the long run this only helps the

jihadis find more recruits. In some ways the origins of the Afghan and Pakistan

Taliban movements lie in a revolutionary politics demanding the overthrow of the

tribal structures. There is no doubt about the intensity of this contest. It is

reckoned that over the last decade the Pakistani Taliban have killed nearly a

thousand tribal elders.

The ethnic, religious and tribal affiliations in the Pashtun areas are not

always easy to disentangle. Take Jalalludin Haqqani, the man who has overseen

the growth of the Haqqani network, a formidable military force that over four

decades has worked with a wide range of international jihadi organisations, al-Qaida,

Pakistan, the UAE and both the Afghan and Pakistan Taliban movements. It has

also sometimes acted as a mediator between them. It has fought against both the

Soviet Union and the United States with considerable success. Haqqani supports

his military activities with a diverse international business that ranges from

scrap metal to hostage-taking. At one point he even had a private airport. Four

of his children have been killed: two by drones; one by US ground forces in

eastern Afghanistan; one in mysterious circumstances last year in Islamabad. The

Haqqanis first stood out from the other tribal leaders when they encouraged Arab

volunteers to join the anti-Soviet struggle in Afghanistan. One of Jalalludin’s

early recruits was Osama bin Laden and it could be said that the Haqqanis

pioneered global jihad before bin Laden had even thought of it. The network has

hosted jihadis from China, Chechnya, Central Asia and Europe. Because of its

might and its international approach to business and conflict, the Haqqani

network has been a close ally of the Afghan Taliban but has never been subsumed

by it.

As well as its bases in eastern Afghanistan, the Haqqani network has religious

and military training facilities on the Pakistani side of the Durand Line, and

so has needed to stay on good terms with the Pakistani state. It has achieved

this by providing services: in the 1990s it trained militants to fight as

Pakistani state proxies in Kashmir; more recently it has bombed Indian and US

targets in Afghanistan – in some cases with the connivance of the ISI. One of

these attacks, in 2011, involved a truckload of explosives sent by the Haqqanis

from Pakistan to a Nato base in Afghanistan. The Americans had intelligence

about the truck and asked Pakistan to stop it. Despite assurances from

Pakistan’s chief of army staff, General Kayani, the truck continued into

Afghanistan. The Americans were monitoring its progress using spy drones but the

Haqqanis outwitted them by switching vehicles in a tunnel. The truck bomb

wounded 77 US personnel.

The US became so frustrated by the Pakistani state’s links to the Haqqani

network that in 2011, despite America’s longstanding effort to keep up

appearances in its relationship with Pakistan, the chairman of the joint chiefs

of staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, could contain himself no longer. ‘The Haqqani

network,’ he complained to the US Senate Armed Services Committee, ‘acts as a

veritable arm of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency.’ In 2012,

Washington put the Haqqani network on its list of designated terrorist

organisations. The Pakistani state, however, continued to allow it freedom of

action, even overlooking its close relations with the Pakistani Taliban. Having

cleared the Pakistani Taliban from six of the seven tribal areas – in a series

of campaigns that led to the deaths of five thousand Pakistani soldiers – the

high command in Rawalpindi failed for years to mount a final offensive in the

one place that remained in militants’ hands: North Waziristan. It wanted to

allow the Haqqani network’s operations there to continue without disruption.

When the offensive finally took place earlier this year, the Haqqanis were given

sufficient warning to enable them to slip to the relative safety of Afghanistan.

In The Pashtun Question, Abubakar Siddique, a correspondent for Radio Free

Europe, argues that if the Pashtuns had been able to govern themselves from 1947

they might have drawn on moderate indigenous traditions represented by figures

such as Pir Roshan, a 16th-century cleric whose opposition to the Mughals

unified the tribes. Roshan gave the Pashtun language a script, introduced

external intellectual influences and accepted Sufi interpretations of sharia.

That Pashtun society moved in a less tolerant direction was a result of the new

Pakistani state’s sense of insecurity. Karachi (the first capital) and later

Islamabad had an interest in encouraging less benign strains of thinking. The

Pakistan military backed successive jihads against Kabul, partly as a way of

resisting Afghan attempts to undermine the Durand Line, and having become a tool

of Pakistani policy, the jihadis were empowered for decades by the huge levels

of funding – an estimated $20 billion – that flowed in from the US and Saudi

Arabia during the anti-Soviet struggle. By sponsoring religious parties and

establishing a network of madrasas to train up zealous cannon fodder, Islamabad

created the conditions in which not only the Taliban but also al-Qaida could

flourish.

On this account, the creation of Pakistan, rather than emancipating the Pashtuns,

simply replaced one set of outside rulers with another. For Siddique, the

entrenchment of regressive power structures by a succession of outsiders is a

better explanation for what is going on than the alternative argument that the

roots of jihadism in the borderlands lie in the predisposition of the tribesmen

to violence. Westerners misunderstand Pashtun society, Siddique argues, in part

because they are often fixated on romantic ideas about Pashtunwali – the tribal

code that is said to prize honour, revenge and hospitality above all other

virtues. Understandably irritated that British imperialists and today’s foreign

correspondents have reduced his culture to an Orientalist fantasy, Siddique

points out that, far from relishing the chance to murder one another, most

Pashtuns, just like everyone else, would be very happy to live in peace. As for

Pashtunwali, as well as allowing for the violent resolution of disputes, its

traditions include taking decisions after broad consultation and discussion

aimed at finding consensus.

Hassan Abbas, a former police officer in north-west Pakistan, also objects to

those who see the Pashtuns as ferocious tribesmen with traditions and attitudes

at odds with the modern world. In The Taliban Revival, he offers rational

explanations for their having fought against the British, the Soviets and the

Americans: the Pashtuns have a culture of resisting invaders, he writes, because

they have always lived on the edge of other people’s empires and so have been

invaded with remarkable frequency.

The Afghan Taliban, Abbas argues, was able to re-emerge after its defeat in 2001

for a number of reasons, including the presence of US forces in Afghanistan and

the profits being made by criminals associated with the organisation. As for the

Pakistani Taliban, it drew strength from the lack of state control in the tribal

areas and, for some years, from Musharraf’s ambiguous policy of supporting those

elements of the Taliban movements which he thought could further Pakistani

interests. Both Talibans were helped by Saudi funding and by the Pakistani

concern that trumped all other considerations: the fear of growing Indian

influence in Afghanistan and Balochistan. But while Pakistan was busy bolstering

the Afghan Taliban to counter the Indians, it found that the Pakistani Taliban

was an increasing problem. Islamabad was comfortable with the Afghan Taliban’s

objective of getting back into power in Kabul, but had trouble containing the

Pakistani Taliban’s growing independence. Some ISI officers shared Mullah Omar’s

frustration with the Pakistani Taliban fighters who refused to rally to his

Afghan cause. As Abbas points out, recruits for the Pakistani Taliban have been

drawn not just from the Pashtun belt but from all over Pakistan. Sectarian

militants from Punjab and alumni from Karachi’s radical madrasas joined up not

to fight alongside Pashtuns and against the US, but to topple the Pakistani

government and establish religious rule in Islamabad and beyond. The strategic

and ideological differences between the two Talibans manifest themselves in many

ways. The more ideological and internationalist Pakistani Taliban, for example,

has opposed polio vaccinations; the more pragmatic Afghan Taliban has been much

more willing to allow UN health teams to do their work.

When foreigners consider Siddique’s ‘Pashtun question’ they tend to do so in the

hope that resolving conflict in the Pashtun belt will make the West safer.

Pashtuns want the question answered for different reasons. They want to escape

the poverty and insecurity that has plagued and brutalised several generations.

It isn’t just that a great many Pashtuns have been killed over the last century:

even more have been dispersed. There are now more Pashtuns living in Karachi

than in Peshawar or Kandahar. Wherever they live, many would agree with Siddique

that the answer lies in economic development.

But Pashtun nationalists face a contradiction. Siddique argues that more should

be done to incorporate the Pashtuns into regular state structures: for one

thing, laws that apply in the rest of Pakistan should replace the repressive

Frontier Crimes Regulation. But any process of political modernisation and

reform will necessarily include the acceptance of the Durand Line as the

international border. Modern states exist only because they have borders that

they police. But this would entrench the division of the Pashtun people.

Siddique tries to get round the problem by proposing the recognition of the line

as a border but allowing free movement across it. It’s a solution that can’t

work: as long as militants are able to cross the border more freely than the two

states’ security personnel, the Taliban movements will maintain a crucial

advantage. Mullah Omar is based in Pakistan and the Pakistani Taliban’s leader,

Mullah Fazlullah, operates from Afghanistan. Distrust between the governments in

Kabul and Islamabad is so acute that the intelligence agencies of both sides are

happy to host each other’s enemies.

Governments in the Middle East and North Africa are using different methods to

try to control religious movements with political ambitions. In Syria, the

Assads have massacred them. In Egypt, Sisi has imprisoned them. In Tunisia,

Gannouchi is trying to use politics to outwit them. But in Pakistan and

Afghanistan, despite everything that’s been thrown at them, the two Talibans are

still standing. The Pashtuns have suffered decades of conflict and few expect

that the US withdrawal from Afghanistan will bring an end to internal strife.

Iran, India and China are already being drawn in to fill the vacuum left by the

US. If history is any guide they will each back different warlords in an attempt

to maintain influence or at least to prevent others from getting influence over

the government in Kabul. And once again the Pashtuns will be caught in the

crossfire.

Travel & Culture Services Pakistan

Online Hotel Booking

| Home | Tours

| Conferences & Incentives | Hotels | Islamabad | Karachi | Lahore | Peshawar| Quetta | Multan | Hyderabad | Hunza

| Gilgit | Chitral | Swat | Karakorum Highway | History | Archeology | Weather | Security | Contact Information |

Advertise on this site click for advertising rates