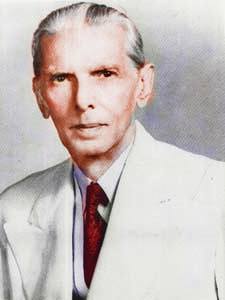

Quaid E Azam

Mohammad Ali Jinnah

The founder of Pakistan the father of nation and the leader of

Indian Muslims

Father of the Nation Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah's achievement as the founder of Pakistan,

dominates everything else he did in his long and crowded public life spanning some 42

years. Yet, by any standard, his was an eventful life, his personality multidimensional

and his achievements in other fields were many, if not equally great. Indeed, several were

the roles he had played with distinction: at one time or another, he was one of the

greatest legal luminaries India had produced during the first half of the century, anambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity, a great constitutionalist, a distinguished

parliamentarian, a top-notch politician, an indefatigable freedom-fighter, a dynamic

Muslim leader, a political strategist and, above all one of the great nation-builders of

modern times. What, however, makes him so remarkable is the fact that while similar other

leaders assumed the leadership of traditionally well-defined nations and espoused their

cause, or led them to freedom, he created a nation out of an inchoate and down-trodden

minority and established a cultural and national home for it. And all that within a

decade.

Father of the Nation Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah's achievement as the founder of Pakistan,

dominates everything else he did in his long and crowded public life spanning some 42

years. Yet, by any standard, his was an eventful life, his personality multidimensional

and his achievements in other fields were many, if not equally great. Indeed, several were

the roles he had played with distinction: at one time or another, he was one of the

greatest legal luminaries India had produced during the first half of the century, anambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity, a great constitutionalist, a distinguished

parliamentarian, a top-notch politician, an indefatigable freedom-fighter, a dynamic

Muslim leader, a political strategist and, above all one of the great nation-builders of

modern times. What, however, makes him so remarkable is the fact that while similar other

leaders assumed the leadership of traditionally well-defined nations and espoused their

cause, or led them to freedom, he created a nation out of an inchoate and down-trodden

minority and established a cultural and national home for it. And all that within a

decade.

For over three decades before the successful culmination in 1947, of the Muslim

struggle for freedom in the South-Asian subcontinent, Jinnah had provided political

leadership to the Indian Muslims: initially as one of the leaders, but later, since 1947,

as the only prominent leader- the Quaid-i-Azam. For over thirty years, he had guided their

affairs; he had given expression, coherence and direction to their legitimate aspirations

and cherished dreams; he had formulated these into concrete demands; and, above all, he

had striven all the while to get them conceded by both the ruling British and the numerous

Hindus the dominant segment of India's population. And for over thirty years he had

fought, relentlessly and inexorably, for the inherent rights of the Muslims for an

honorable existence in the subcontinent. Indeed, his life story constitutes, as it were,

the story of the rebirth of the Muslims of the subcontinent and their spectacular rise to

nationhood, phoenix like.

Early Life

Born on December 25, 1876, in

a prominent mercantile family in Jherak Sindh (130 Kilometers North East of

Karachi). After fist few years of education at the government School in Jherak

his family came to Karachi and he was admitted into the Sindh Madrassat-ul-Islam

where he studied till 8th class and was later on admitted into the Christian

Mission School in Karachi.

His father was a prosperous merchant who had been born to a

family of weavers in the village of Paneli in the princely state of Gondal (Kathiawar,

Gujarat India); his mother was also of that village. They had moved to Sindh in

1875, having married before their migration. Karachi was having an economic boom

at that time: the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 meant it was 200 nautical

miles closer to Europe for shipping than Bombay. Jinnah's family was of the

Ismaili Khoja branch of Shi'a Islam though Jinnah later followed the

Twelver Shi'a teachings. Jinnah was the second child; he had three brothers and

three sisters, including his younger sister Fatima Jinnah. The spoke, Kutchi and

English. Except for Fatima, little is known of his siblings, where they settled

or if they met with their brother as he advanced in his legal and political

careers.

As a boy, Jinnah lived for a time in Bombay with an aunt and

may have attended the Gokal Das Tej Primary School there, later on studying at

the Cathedral and John Connon School. In Karachi, he attended the

Sindh-Madrasa-tul-Islam and the Christian Missionary Society High

School. He gained his matriculation from Bombay University at the

high school. In his later years and especially after his death, a large number

of stories about the boyhood of Pakistan's founder were circulated: that he

spent all his spare time at the police court, listening to the proceedings, and

that he studied his books by the glow of street lights for lack of other

illumination. His official biographer, Hector Bolitho, writing in 1954,

interviewed surviving boyhood associates, and obtained a tale that the young Jinnah discouraged other children from playing marbles in the dust, urging them

to rise up, keep their hands and clothes clean, and play cricket instead.

Early Life in England

Jinnah joined the Lincoln's Inn in 1893 to

become the youngest Indian to be called to the Bar, three years later. Starting out in the

legal profession with nothing to fall back upon except his native ability and

determination, young Jinnah rose to prominence and became Bombay's most successful lawyer,

as few did, within a few years. Once he was firmly established in the legal profession,

Jinnah formally entered politics in 1905 from the platform of the Indian National

Congress. He went to England in that year alongwith Gopal Krishna Gokhale (1866-1915), as

a member of a Congress delegation to plead the cause of Indian self-government during the

British elections. A year later, he served as Secretary to Dadabhai Noaroji(1825-1917),

the then Indian National Congress President, which was considered a great honour for a

budding politician. Here, at the Calcutta Congress session (December 1906), he also made

his first political speech in support of the resolution on self-government.

Political Career

Three

years later, in January 1910, Jinnah was elected to the newly-constituted Imperial

Legislative Council. All through his parliamentary career, which spanned some four

decades, he was probably the most powerful voice in the cause of Indian freedom and Indian

rights. Jinnah, who was also the first Indian to pilot a private member's Bill through the

Council, soon became a leader of a group inside the legislature. Mr. Montagu (1879-1924),

Secretary of State for India, at the close of the First World War, considered Jinnah

"perfect mannered, impressive-looking, armed to the teeth with

dialectics..."Jinnah, he felt, "is a very clever man, and it is, of course, an

outrage that such a man should have no chance of running the affairs of his own

country.

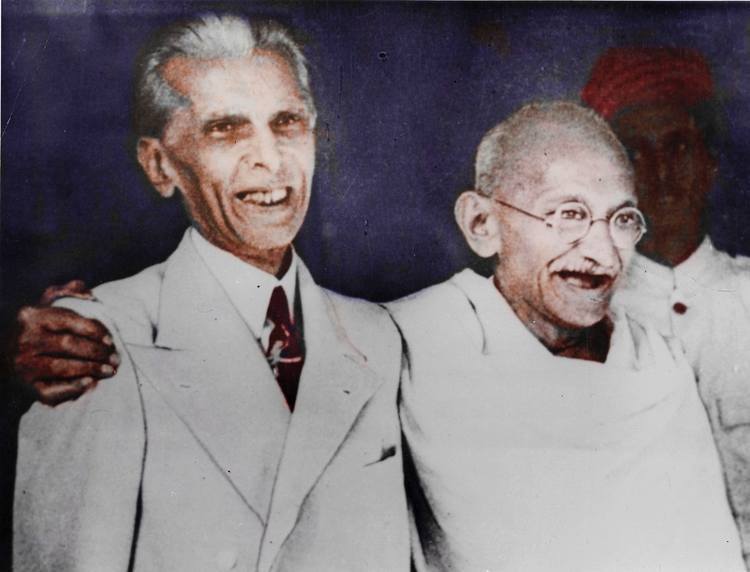

For about

three decades since his entry into politics in 1906, Jinnah passionately believed in and

assiduously worked for Hindu-Muslim unity. Gokhale, the foremost Hindu leader before

Gandhi, had once said of him, "He has the true stuff in him and that freedom from all

sectarian prejudice which will make him the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity: And, to

be sure, he did become the architect of Hindu-Muslim Unity: he was responsible for the

Congress-League Pact of 1916, known popularly as Lucknow Pact- the only pact ever signed

between the two political organisations, the Congress and the All-India Muslim League,

representing, as they did, the two major communities in the subcontinent.

The

Congress-League scheme embodied in this pact was to become the basis for the

Montagu-Chemlsford Reforms, also known as the Act of 1919. In retrospect, the Lucknow Pact

represented a milestone in the evolution of Indian politics. For one thing, it conceded

Muslims the right to separate electorate, reservation of seats in the legislatures and

weightage in representation both at the Centre and the minority provinces. Thus, their

retention was ensured in the next phase of reforms. For another, it represented a tacit

recognition of the All-India Muslim League as the representative organisation of the

Muslims, thus strengthening the trend towards Muslim individuality in Indian politics. And

to Jinnah goes the credit for all this. Thus, by 1917, Jinnah came to be recognised among

both Hindus and Muslims as one of India's most outstanding political leaders. Not only was

he prominent in the Congress and the Imperial Legislative Council, he was also the

President of the All-India Muslim and that of the Bombay Branch of the Home Rule League.

More important, because of his key-role in the Congress-League entente at Lucknow, he was

hailed as the ambassador, as well as the embodiment, of Hindu-Muslim unity.

Constitutional

Struggle

In

subsequent years, however, he felt dismayed at the injection of violence into politics.

Since Jinnah stood for "ordered progress", moderation, gradualism and

constitutionalism, he felt that political terrorism was not the pathway to national

liberation but, the dark alley to disaster and destruction. Hence, the constitutionalist

Jinnah could not possibly, countenance Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's novel methods of

Satyagrah (civil disobedience) and the triple boycott of government-aided schools and

colleges, courts and councils and British textiles. Earlier, in October 1920, when Gandhi,

having been elected President of the Home Rule League, sought to change its constitution

as well as its nomenclature, Jinnah had resigned from the Home Rule League, saying:

"Your extreme programme has for the moment struck the imagination mostly of the

inexperienced youth and the ignorant and the illiterate. All this means disorganisation

and chaos". Jinnah did not believe that ends justified the means.

In the

ever-growing frustration among the masses caused by colonial rule, there was ample cause

for extremism. But, Gandhi's doctrine of non-cooperation, Jinnah felt, even as

Rabindranath Tagore(1861-1941) did also feel, was at best one of negation and despair: it

might lead to the building up of resentment, but nothing constructive. Hence, he opposed

tooth and nail the tactics adopted by Gandhi to exploit the Khilafat and wrongful tactics

in the Punjab in the early twenties. On the eve of its adoption of the Gandhian programme,

Jinnah warned the Nagpur Congress Session (1920): "you are making a declaration (of

Swaraj within a year) and committing the Indian National Congress to a programme, which

you will not be able to carry out". He felt that there was no short-cut to

independence and that Gandhi's extra-constitutional methods could only lead to political

terrorism, lawlessness and chaos, without bringing India nearer to the threshold of

freedom.

The

future course of events was not only to confirm Jinnah's worst fears, but also to prove

him right. Although Jinnah left the Congress soon thereafter, he continued his efforts

towards bringing about a Hindu-Muslim entente, which he rightly considered "the most

vital condition of Swaraj". However, because of the deep distrust between the two

communities as evidenced by the country-wide communal riots, and because the Hindus failed

to meet the genuine demands of the Muslims, his efforts came to naught. One such effort

was the formulation of the Delhi Muslim Proposals in March, 1927. In order to bridge

Hindu-Muslim differences on the constitutional plan, these proposals even waived the

Muslim right to separate electorate, the most basic Muslim demand since 1906, which though

recognised by the congress in the Lucknow Pact, had again become a source of friction

between the two communities. surprisingly though, the Nehru Report (1928), which

represented the Congress-sponsored proposals for the future constitution of India, negated

the minimum Muslim demands embodied in the Delhi Muslim Proposals.

In vain

did Jinnah argue at the National convention (1928): "What we want is that Hindus and

Mussalmans should march together until our object is achieved...These two communities have

got to be reconciled and united and made to feel that their interests are common".

The Convention's blank refusal to accept Muslim demands represented the most devastating

setback to Jinnah's life-long efforts to bring about Hindu-Muslim unity, it meant

"the last straw" for the Muslims, and "the parting of the ways" for

him, as he confessed to a Parsee friend at that time. Jinnah's disillusionment at the

course of politics in the subcontinent prompted him to migrate and settle down in London

in the early thirties. He was, however, to return to India in 1934, at the pleadings of

his co-religionists, and assume their leadership. But, the Muslims presented a sad

spectacle at that time. They were a mass of disgruntled and demoralised men and women,

politically disorganised and destitute of a clear-cut political programme.

Muslim

League Reorganized

Thus, the

task that awaited Jinnah was anything but easy. The Muslim League was dormant: primary

branches it had none; even its provincial organisations were, for the most part,

ineffective and only nominally under the control of the central organisation. Nor did the

central body have any coherent policy of its own till the Bombay session (1936), which

Jinnah organised. To make matters worse, the provincial scene presented a sort of a jigsaw

puzzle: in the Punjab, Bengal, Sindh, the North West Frontier, Assam, Bihar and the United

Provinces, various Muslim leaders had set up their own provincial parties to serve their

personal ends. Extremely frustrating as the situation was, the only consolation Jinnah had

at this juncture was in Allama Iqbal(1877-1938), the poet-philosopher, who stood steadfast

by him and helped to charter the course of Indian politics from behind the scene.

Undismayed

by this bleak situation, Jinnah devoted himself with singleness of purpose to organising

the Muslims on one platform. He embarked upon country-wide tours. He pleaded with

provincial Muslim leaders to sink their differences and make common cause with the League.

He exhorted the Muslim masses to organise themselves and join the League. He gave

coherence and direction to Muslim sentiments on the Government of India Act, 1935. He

advocated that the Federal Scheme should be scrapped as it was subversive of India's

cherished goal of complete responsible Government, while the provincial scheme, which

conceded provincial autonomy for the first time, should be worked for what it was worth,

despite its certain objectionable features. He also formulated a viable League manifesto

for the election scheduled for early 1937. He was, it seemed, struggling against time to

make Muslim India a power to be reckoned with.

Despite

all the manifold odds stacked against it, the Muslim Leauge won some 108 (about 23 per

cent) seats out of a total of 485 Muslim seats in the various legislature. Though not very

impressive in itself, the League's partial success assumed added significance in view of

the fact that the League won the largest number of Muslim seats and that it was the only

all-India party of the Muslims in the country. Thus, the elections represented the first

milestone on the long road to putting Muslim India on the map of the subcontinent.

Congress in Power With the year 1937 opened the most momentous decade in modern Indian

history. In that year came into force the provincial part of the Government of India Act,

1935, granting autonomy to Indians for the first time, in the provinces.

The

Congress, having become the dominant party in Indian politics, came to power in seven

provinces exclusively, spurning the League's offer of cooperation, turning its back

finally on the coalition idea and excluding Muslims as a political entity from the portals

of power. In that year, also, the Muslim League, under Jinnah's dynamic leadership, was

reorganised de novo, transformed into a mass organisation, and made the spokesman of

Indian Muslims as never before. Above all, in that momentous year were initiated certain

trends in Indian politics, the crystallisation of which in subsequent years made the

partition of the subcontinent inevitable. The practical manifestation of the policy of the

Congress which took office in July, 1937, in seven out of eleven provinces, convinced

Muslims that, in the Congress scheme of things, they could live only on sufferance of

Hindus and as "second class" citizens. The Congress provincial governments, it

may be remembered, had embarked upon a policy and launched a programme in which Muslims

felt that their religion, language and culture were not safe. This blatantly aggressive

Congress policy was seized upon by Jinnah to awaken the Muslims to a new consciousness,

organize them on all-India platform, and make them a power to be reckoned with. He also

gave coherence, direction and articulation to their innermost, yet vague, urges and

aspirations. Above all, the filled them with his indomitable will, his own unflinching

faith in their destiny.

The

New Awakening

As a

result of Jinnah's ceaseless efforts, the Muslims awakened from what Professor Baker

calls(their) "unreflective silence" (in which they had so complacently basked

for long decades), and to "the spiritual essence of nationality" that had

existed among them for a pretty long time. Roused by the impact of successive Congress

hammerings, the Muslims, as Ambedkar (principal author of independent India's

Constitution) says, "searched their social consciousness in a desperate attempt to

find coherent and meaningful articulation to their cherished yearnings. To their great

relief, they discovered that their sentiments of nationality had flamed into

nationalism". In addition, not only had they developed" the will to live as a

"nation", had also endowed them with a territory which they could occupy and

make a State as well as a cultural home for the newly discovered nation. These two

pre-requisites, as laid down by Renan, provided the Muslims with the intellectual

justification for claiming a distinct nationalism (apart from Indian or Hindu nationalism)

for themselves. So that when, after their long pause, the Muslims gave expression to their

innermost yearnings, these turned out to be in favour of a separate Muslim nationhood and

of a separate Muslim state.

Demand for Pakistan

"We

are a nation", they claimed in the ever eloquent words of the Quaid-i-Azam- "We

are a nation with our own distinctive culture and civilization, language and literature,

art and architecture, names and nomenclature, sense of values and proportion, legal laws

and moral code, customs and calendar, history and tradition, aptitudes and ambitions; in

short, we have our own distinctive outlook on life and of life. By all canons of

international law, we are a nation". The formulation of the Muslim demand for

Pakistan in 1940 had a tremendous impact on the nature and course of Indian politics. On

the one hand, it shattered for ever the Hindu dreams of a pseudo-Indian, in fact, Hindu

empire on British exit from India: on the other, it heralded an era of Islamic renaissance

and creativity in which the Indian Muslims were to be active participants. The Hindu

reaction was quick, bitter, malicious.

Equally

hostile were the British to the Muslim demand, their hostility having stemmed from their

belief that the unity of India was their main achievement and their foremost contribution.

The irony was that both the Hindus and the British had not anticipated the astonishingly

tremendous response that the Pakistan demand had elicited from the Muslim masses. Above

all, they failed to realize how a hundred million people had suddenly become supremely

conscious of their distinct nationhood and their high destiny. In channeling the course of

Muslim politics towards Pakistan, no less than in directing it towards its consummation in

the establishment of Pakistan in 1947, non played a more decisive role than did

Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah. It was his powerful advocacy of the case of Pakistan and

his remarkable strategy in the delicate negotiations, that followed the formulation of the

Pakistan demand, particularly in the post-war period, that made Pakistan inevitable.

Cripps

Scheme

While the

British reaction to the Pakistan demand came in the form of the Cripps offer of April,

1942, which conceded the principle of self-determination to provinces on a territorial

basis, the Rajaji Formula (called after the eminent Congress leader C.Rajagopalacharia,

which became the basis of prolonged Jinnah-Gandhi talks in September, 1944), represented

the Congress alternative to Pakistan. The Cripps offer was rejected because it did not

concede the Muslim demand the whole way, while the Rajaji Formula was found unacceptable

since it offered a "moth-eaten, mutilated" Pakistan and the too appended with a

plethora of pre-conditions which made its emergence in any shape remote, if not altogether

impossible. Cabinet Mission The most delicate as well as the most tortuous negotiations,

however, took place during 1946-47, after the elections which showed that the country was

sharply and somewhat evenly divided between two parties- the Congress and the League- and

that the central issue in Indian politics was Pakistan.

These

negotiations began with the arrival, in March 1946, of a three-member British Cabinet

Mission. The crucial task with which the Cabinet Mission was entrusted was that of

devising in consultation with the various political parties, a constitution-making

machinery, and of setting up a popular interim government. But, because the

Congress-League gulf could not be bridged, despite the Mission's (and the Viceroy's)

prolonged efforts, the Mission had to make its own proposals in May, 1946. Known as the

Cabinet Mission Plan, these proposals stipulated a limited centre, supreme only in foreign

affairs, defence and communications and three autonomous groups of provinces. Two of these

groups were to have Muslim majorities in the north-west and the north-east of the

subcontinent, while the third one, comprising the Indian mainland, was to have a Hindu

majority. A consummate statesman that he was, Jinnah saw his chance. He interpreted the

clauses relating to a limited centre and the grouping as "the foundation of

Pakistan", and induced the Muslim League Council to accept the Plan in June 1946; and

this he did much against the calculations of the Congress and to its utter dismay.

Tragically

though, the League's acceptance was put down to its supposed weakness and the Congress put

up a posture of defiance, designed to swamp the Leauge into submitting to its dictates and

its interpretations of the plan. Faced thus, what alternative had Jinnah and the League

but to rescind their earlier acceptance, reiterate and reaffirm their original stance, and

decide to launch direct action (if need be) to wrest Pakistan. The way Jinnah manoeuvred

to turn the tide of events at a time when all seemed lost indicated, above all, his

masterly grasp of the situation and his adeptness at making strategic and tactical moves.

Partition Plan By the close of 1946, the communal riots had flared up to murderous

heights, engulfing almost the entire subcontinent. The two peoples, it seemed, were

engaged in a fight to the finish. The time for a peaceful transfer of power was fast

running out. Realising the gravity of the situation. His Majesty's Government sent down to

India a new Viceroy- Lord Mountbatten. His protracted negotiations with the various

political leaders resulted in 3 June.(1947) Plan by which the British decided to partition

the subcontinent, and hand over power to two successor States on 15 August, 1947. The plan

was duly accepted by the three Indian parties to the dispute- the Congress the League and

the Akali Dal(representing the Sikhs).

Leader

of a Free Nation

In

recognition of his singular contribution, Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah was nominated

by the Muslim League as the Governor-General of Pakistan, while the Congress appointed

Mountbatten as India's first Governor-General. Pakistan, it has been truly said, was born

in virtual chaos. Indeed, few nations in the world have started on their career with less

resources and in more treacherous circumstances. The new nation did not inherit a central

government, a capital, an administrative core, or an organized defence force. Its social

and administrative resources were poor; there was little equipment and still less

statistics. The Punjab holocaust had left vast areas in a shambles with communications

disrupted. This, alongwith the en masse migration of the Hindu and Sikh business and

managerial classes, left the economy almost shattered.

The

treasury was empty, India having denied Pakistan the major share of its cash balances. On

top of all this, the still unorganized nation was called upon to feed some eight million

refugees who had fled the insecurities and barbarities of the north Indian plains that

long, hot summer. If all this was symptomatic of Pakistan's administrative and economic

weakness, the Indian annexation, through military action in November 1947, of Junagadh

(which had originally acceded to Pakistan) and the Kashmir war over the State's accession

(October 1947-December 1948) exposed her military weakness. In the circumstances,

therefore, it was nothing short of a miracle that Pakistan survived at all. That it

survived and forged ahead was mainly due to one man-Muhammad Ali Jinnah. The nation

desperately needed in the person of a charismatic leader at that critical juncture in the

nation's history, and he fulfilled that need profoundly. After all, he was more than a

mere Governor-General: he was the Quaid-i-Azam who had brought the State into being.

In the

ultimate analysis, his very presence at the helm of affairs was responsible for enabling

the newly born nation to overcome the terrible crisis on the morrow of its cataclysmic

birth. He mustered up the immense prestige and the unquestioning loyalty he commanded

among the people to energize them, to raise their morale, land directed the profound

feelings of patriotism that the freedom had generated, along constructive channels. Though

tired and in poor health, Jinnah yet carried the heaviest part of the burden in that first

crucial year. He laid down the policies of the new state, called attention to the

immediate problems confronting the nation and told the members of the Constituent

Assembly, the civil servants and the Armed Forces what to do and what the nation expected

of them. He saw to it that law and order was maintained at all costs, despite the

provocation that the large-scale riots in north India had provided. He moved from Karachi

to Lahore for a while and supervised the immediate refugee problem in the Punjab. In a

time of fierce excitement, he remained sober, cool and steady. He advised his excited

audience in Lahore to concentrate on helping the refugees, to avoid retaliation, exercise

restraint and protect the minorities. He assured the minorities of a fair deal, assuaged

their inured sentiments, and gave them hope and comfort. He toured the various provinces,

attended to their particular problems and instilled in the people a sense of belonging. He

reversed the British policy in the North-West Frontier and ordered the withdrawal of the

troops from the tribal territory of Waziristan, thereby making the Pathans feel themselves

an integral part of Pakistan's body-politics. He created a new Ministry of States and

Frontier Regions, and assumed responsibility for ushering in a new era in Balochistan. He

settled the controversial question of the states of Karachi, secured the accession of

States, especially of Kalat which seemed problematical and carried on negotiations with

Lord Mountbatten for the settlement of the Kashmir Issue.

The

Quaid's last Message

It was,

therefore, with a sense of supreme satisfaction at the fulfillment of his mission that

Jinnah told the nation in his last message on 14 August, 1948: "The foundations of

your State have been laid and it is now for you to build and build as quickly and as well

as you can". In accomplishing the task he had taken upon himself on the morrow of

Pakistan's birth, Jinnah had worked himself to death, but he had, to quote Richard Symons,

"contributed more than any other man to Pakistan's survival". He died on 11

September, 1948. How true was Lord Pethick Lawrence, the former Secretary of State for

India, when he said, "Gandhi died by the hands of an assassin; Jinnah died by his

devotion to Pakistan".

A man

such as Jinnah, who had fought for the inherent rights of his people all through his life

and who had taken up the somewhat unconventional and the largely misinterpreted cause of

Pakistan, was bound to generate violent opposition and excite implacable hostility and was

likely to be largely misunderstood. But what is most remarkable about Jinnah is that he

was the recipient of some of the greatest tributes paid to any one in modern times, some

of them even from those who held a diametrically opposed viewpoint.

The Aga Khan

considered him "the greatest man he ever met", Beverley Nichols, the author of

`Verdict on India', called him "the most important man in Asia", and Dr.

Kailashnath Katju, the West Bengal Governor in 1948, thought of him as "an

outstanding figure of this century not only in India, but in the whole world". While

Abdul Rahman Azzam Pasha, Secretary General of the Arab League, called him "one of

the greatest leaders in the Muslim world", the Grand Mufti of Palestine considered

his death as a "great loss" to the entire world of Islam. It was, however, given

to Surat Chandra Bose, leader of the Forward Bloc wing of the Indian National Congress, to

sum up succinctly his personal and political achievements. "Mr Jinnah",he said

on his death in 1948, "was great as a lawyer, once great as a Congressman, great as a

leader of Muslims, great as a world politician and diplomat, and greatest of all as a man

of action, By Mr. Jinnah's passing away, the world has lost one of the greatest statesmen

and Pakistan its life-giver, philosopher and guide". Such was Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad

Ali Jinnah, the man and his mission, such the range of his accomplishments and

achievements.

Extract from Address to Public Servants at Chittagong on 25th March

You should not be influenced by any

political pressure, by any political party or individual politician. If you want to raise

the prestige and greatness of Pakistan, you must not fall a victim to any pressure but do

your duty as servants to the people and the state, fearlessly and honestly. Service is the

backbone of the state. Governments are formed, governments are defeated, Prime Ministers

come and go, Ministers come and go, but you stay on, and therefore, there is a very great

responsibility placed on your shoulders.

Make the people feel that you are their

servants and friends, maintain the highest standard of honour, integrity, justice and fair

play. Work honestly and sincerely."

Extract

from Address to Public Servants at Government House Peshawar on 14 April, 1948.

"You should not be influenced by any

political pressure, by any party or individual. If you want to raise the prestige and

greatness of Pakistan, do you duty as servants to the people and the Stat, fearlessly and

honestly. Governments are formed, governments are defeated, Prime Ministers come and go.

Ministers come and go, but you stay on, and therefore, there is a very great

responsibility placed on your shoulders. Whichever Government is formed according to the

constitution you duty is not only to serve loyally and faithfully, but, at the same time,

fearlessly maintaining your high reputation, your prestige, your honour and the integrity

of your service."

Advertise on this site click for advertising rates